.

Published in the Fall of 2014 by Transaction Press, The City is a significantly revised and expanded second edition of my 1984 survey of reference to the city and urban life in fiction and nonfiction literature that remained in print for twelve years. That edition was revised and expanded, translated into Chinese, and published by the Chinese Architectural and Engineering Press in 2010. The Chinese edition came about as a result of the wish of Professor Liangyong Wu of Tsinghua University in Beijing, who purchased the first edition several years ago in the US, to have the book translated into Chinese.

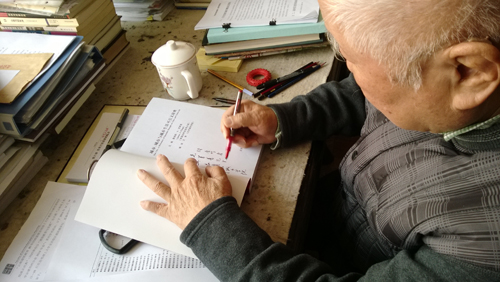

Professor Wu, who is perhaps the most renowned professor of city planning in China, inscribes a copy of the Chinese edition. The inscription says it is “to the original author” and he hopes I approve of it.

The Beijing Lecture Group

One outgrowth of my book was an invitation to give a series of lectures on American city planning to professors at Beijing City University in 2008. Above is a photo of those whjo were instrumental in arranmging the series, among them, (Front row second from left) is Prof. Wu and (econd from right) the President of Beijing City U. The translater of the book, (back row, second from left) is Prof. Wang Yu. The lectures were videotaped and translated and subsequently published in the university journal.

The new 2014 English edition contains over 400 new references covering changes in urbanism from the 1980s to the present, expanded essays, expanded indexes, and new illustrations. Designed as a reference for writers and others seeking quotable material about cities and urban life, and specific cities, the book provides a one-of-a-kind resource that surveys literature from ancient times to the present.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

In the three decades since publication of the first edition of The City much has changed. It is also seems true that some things (if we take no heed of Heraclitus) “remain the same.” So, many of the quotations in this book, despite that fact that Aristotle and Shakespeare are still dead, and the Bible retains the same scriptures, retain their relevance (although times and circumstances since place them in a different light and interpretation).

However, as will be evident, the first edition of The City was instrumental in changing its author, and also reconfirming some ways in which he has remained the same. It inspired new academic interests, years of teaching, living and traveling in over seventy countries and, a good deal of writing, upon which I draw widely in these prefatory remarks, the introductory essay and in the additions to this new edition.

* * *

In 2008, the world reached an invisible but momentous milestone: For the first time in history, more than half its population, 3.3 billion people, will be living in urban areas. By 2030, this is expected to swell to almost 5 billion… While the world’s urban population grew very rapidly (from 220 million to 2.8 billion) over the 20th century, the next few decades will see an unprecedented scale of urban growth in the developing world. This will be particularly notable in Africa and Asia where the urban population will double between 2000 and 2030: That is, the accumulated urban growth of these two regions during the whole span of history will be duplicated in a single generation. By 2030, the towns and cities of the developing world will make up 81 per cent of urban humanity. [United Nations State of the World Population Report, 2007]

Even without these statistics, it is evident that in the urban world much has changed in size, form, composition and function of cities in the past three decades. But much has changed in substance as well. At the beginning of the compilation of the first edition of The City China’s political leader Deng Xiaoping was making his pronouncements in China that “it doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white as long as it catches the mouse,” and “to get rich is glorious,” pronouncements he voiced in China’s rapidly urbanizing special economic zones. In subsequent years China has grown to the world’s second-largest economy and may shortly become the largest. Central to this transformation has been China’s major cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, and Guangzhou, among others— that have burgeoned into the tens of millions as migration from the countryside in search of the glorious riches of urban opportunity. Shenzhen, not much more than a fishing village on the border of Hong Kong three decades ago, now approaches a population of twelve million that manufactures and assembles a vast array of American consumer products.

At the personal level these momentous changes have been of special interest to an urbanist with wanderlust. This was the urban world that was forming in full process at the publication of the first edition of The City and as I embarked on some different “adventures in urbanism” than I had received from my formal education and teaching. In 1977 I began organizing and escorting annual tours to cities in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. These travels broadened my interest in urbanism in manifold ways. In particular, it provoked an interest in my switching from the policy-oriented approach to cities that had been the focus of my postgraduate education, as well as my prime instructional responsibilities, to research linking the arts and humanities to the study of cities and urban life. Hence, I began writing about urbanism in a variety of media ranging from journalism to fiction, from the op-ed essay to the documentary script and screenplay. An inveterate habit of my writing has been the use of, or acquisition of the apt, or inspirational quotation about cities and urban life.

The rapidity of urban change past three decades has provided much to compare and contrast. When I first visited China in the early 1980s I most remember as I wandered the streets of Beijing two distinctive sounds: the whirring of bicycle chains and the ching-ching-ing of what seemed to be China’s universal bicycle bell (I liked the sound of the bell so much I bought one for my own bike). Hence, I knew exactly the impression that journalist William Montalbano was relating in his novel set in Beijing:

Seen from a hotel window or a tourist bus, the infinite procession of bicycles is one of China’s most impressive sights. On every major street, broad lanes are reserved for bicycles. Even in downtown Peking they outnumber the trucks and cars by a thousand to one. Alice and her friends rhapsodized about the bicycles. They could talk for hours, insulated in the air-conditioned bus, of the silent, measured stream, as massive and as unstoppable as the Yangtze. They found in the bicycles a symbol of the progressive New China. At faculty teas it would, no doubt, sound quite profound. [“A Death in Beijing,” 1984]

That could have been from the journal of my first visit to Beijing. But in the several subsequent visits those quaint and pleasant “songs” of the bicycle would be increasingly drowned out by the horn blare of the swelling number of automobiles that clogged and smogged the orthogonal capitol’s expanding ripple of ring roads.

A couple years later, in the McDonalds in a western area of Beijing I sat upstairs eating with ye-ye’s, ba-ba’s (grandmothers and grandfathers) and kids and grandkids on a Saturday morning. Under the din of Mandarin I could make out the refrains of the Carpenters, singing (in English of course): “We’ve only just begun / to live. / White lace and promises / A kiss for luck and we’re on our way. / And yes, We’ve just begun.” The incongruity was almost dizzying. The Chinese present probably didn’t understand a word of it and, I was likely to be the only person who knew that nobody needed a Big Mac and super-sized fries more than Karen Carpenter, who sadly, starved herself to death. It was rather ironic for a country that has known numerous famines.

Following my most recent visit to Beijing a month before the Olympics I wrote, in a piece titled “The Forbidding City” on my website: One of the more endearing images I have of Beijing is of a university student peddling down a street on a dilapidated Mao-era Tianjin “Silver Pigeon.” His girlfriend rides side-saddle on the rear carrier, one arm around his waist, the other hand holding a book she is reading while resting her head against his back. There is something romantic about this vision, harkening back to the days when untold numbers of bikes plied Beijing streets with the only the sounds of creaking chains and tinkling warning bells, a vast peloton of placidity. The image I saw [this time was a] couple was nearly wiped out by a $70,000 Mercedes Benz that gave the bike and its riders absolutely no quarter despite being in a bike lane.

That history no doubt forms much of the motivation of a country that has made dizzying economic strides in the span of a generation and in a process that has transformed the urban morphology of all of its major cities. The Chinese were, and are, hell bent on making up for generations of disastrous governments and economic policies and lagging behind the West the urbanization. They have “only just begun,” and it is a rare and privileged experience for an urbanist to witness such urban transformation in so short a span of time.

But herein lies a dilemma. Every student of cities and urban life understands that urbanization is a process a relentless change. With exceptions such as Brugges, or Venice, and a few others, urbanists must accept the Heraclitian reality that the city of today will be different than the city of yesterday, and the city of tomorrow will be different than the city of today. Yet, the urbanist, for reasons ranging from scholarly analysis to aesthetic appreciation, to (dare I say) nostalgia, often hankers for constancy, historic continuity, and authenticity that often result in disappointment.

… China is only one epicenter for an urbanization process that has now become genuinely global, in part through the astonishing global integration of financial markets that use their flexibility to debt finance urban projects from Dubai to São Paulo and from Madrid and Mumbai to Hong Kong and London. The Chinese central bank, for example, has been active in the secondary mortgage market in the US, while Goldman Sachs has been involved in the surging property markets in Mumbai and Hong Kong capital has invested in Baltimore. Almost every city in the world has witnessed a building boom for the rich – often of a distressing similar character – in the midst of a flood of impoverished migrants converging on cities as a rural peasantry is dispossessed through the industrialization and commercialization of agriculture. [David Harvey, Rebel Cities, from the right to the city to the Urban Revolution, 2012]

Even before “globalization” came into our common lexicon American super-brands had been employed as a form of shorthand for the cultural adulteration that comes with the marketing power of international corporations. No long ago a shuttle that I was led to believe would drop me at an indigenous local market in Kelang, Malaysia, plopped me at the entrance to a four-story mall, its central doors situated between those international tutelary gods of American commerce, a McDonald’s and a Pizza Hut. Two young Malaysian guys about to tuck into their McBreakfasts informed me that an authentic market was a thirty-minute cab ride away. When I entered the massive, multi-level mall it only got worse (or better, depending upon your point of view).

Kelang is very proud of its huge, modern, clean air-conditioned mall with just about every familiar international brand name shop you can name and virtually nothing of local production or interest. Even the Muzak droned Western music. I was in a town in Malaysia and in this mall there is not a single sign written in the local language and script. I had traveled maybe two-thirds around the earth and arrived in Orange County.

Malaysians have the right to be proud of their (derivative) commercial modernity; their mall signifies economic success because they can now offer the very same consumer goods you can get in similar malls everywhere. But here the dilemma rises again. Is it proper for those of us who love cities and travel for the contrasting exposure they provide in cultures that are educationally and entertainingly different, but sometimes are backward, impoverished, and suffer from economic and political systems that are oppressive and stifle liberty? Have we any right to prefer that they would retain their undeveloped and primitive status for the sake of our amusement. We may have to accept the inevitability that their adoption of market economies, more civil liberties (?), higher education, and such are going to make them more like us and less and less like peoples who provide us with an interesting foreign experience.

If one travels abroad long enough (in my case forty years is of some sufficiency), especially the last forty years, one cannot help noticing globalism’s rapid and inexorable creep. It took hundreds of thousands of years for cultures to evolve and to take their forms and establish their differentiation. Much of this was done in geographical isolation. Their languages, customs, mores, religions, while not always sui generis, had some degree of integrity and distinction. Even when I first began traveling to Europe in the early 1970s I recall the different currencies, and validity of the adage that “one is able to distinguish the Europeans by [the presumed lesser quality] of their shoes.” Try doing that today.

Much of this global urbanism owes to American commercial hegemony following World War II when many European and Asian cities were in rubble and their economies in ruins. American manufacturing and improvements in production and distribution, abetted by the necessary productivity improvements during the war, gave America a significant advantage in products, fashions, styles, brand identification, and that term later ushered in by Silicon Valley, “market share.” We may have lulled ourselves into the expectation of a permanent commercial hegemony, thanks in part to the fact that our major postwar adversaries, the USSR and China, practiced economic systems ill-suited to the production and marketing of consumer products. But we were soon surprised by the rapid rise of Germany and Japan in the production of competitive automobiles photographic office equipment and other products. What America did retain was the advantage in media, that great transporter of popular culture.

There is an irony to all this merchandising of Western products to the erstwhile Third Worlds. Much of the stuff is either manufactured or assembled nearby or in the country next door. There’s a good deal of debate about the pros and cons of globalism. Workers in sweatshops in Southeast Asia and Indonesia, among other places, might make $.26 an hour, but that might be three times as much as they could make in any other local industry. Then of course there is the social disruption and environmental degradation that often comes along with the Faustian compact that these countries make with Western capitalism. There is reason to doubt that the increases in income provided by working for Nike and the rest of the Western brand names are netted out against the health effects of sweatshops, lack of workplace safety standards, and absence of environmental controls.

There was bound to be “blowback.”

The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges. … In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer who might loose the lightning, New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm. [E.B. White, written in 1949 about New York’s vulnerability in the aftermath of World War II]

White, who added this dark footnote to his great paean to the city, “This is New York,” on the verge of the Cold War. in 1949. But in retrospect of the smoke and cinder of 9-11, White might have been hoping that New York’s “irresistible charms” would win over ideological, not cultural, “perverted dreamer[s].” Rather, to some, the great city had become a symbol of urban/globalism’s insurgent neo-colonial transmission of modernism, democracy, and capitalism’s commodification of culture.

A new concept came into usage, sometimes alongside (perhaps even spawned by) “globalization”—”Ground Zero.” For many centuries the centers of cities had been the safest place, most distant from the city walls, and close to the keep, the armory, and the sanctuary of the cathedral. Indeed the city itself was often the safest place to be in times of weak nation states or failed empires. But that is no longer the case, first in the age of the ICBM, and lately in the age of the individual terrorist as a potential weapon of mass destruction. “Ground Zero,” the center, had become the crosshairs in new and terrible weapons employed in what some has come to refer to as “a clash of civilizations,” but might as aptly be referred to as a clash between the modern, urban, globalized world and its traditional, recalcitrant and often exploited hinterlands. The center is where population is dense and where there is the greatest prospect the greatest destruction in the number of casualties—ground zero.

Massive concentrations of urbanites have elevated the prospects for other terrors as well. Richard Preston, author of The Demon in the Freezer, the non-fiction bio-thriller about smallpox, writes that epidemiologists have figured out that smallpox needs densities of about “two hundred thousand people living within fourteen days travel of one another, or the [smallpox] virus can’t keep its life cycle going, and it dies out.” That level of density was first achieved about seven thousand years ago with city-centered settled agricultural areas. Preston calls smallpox, which is a very virulent and very nasty disease, the “first urban virus.” What is very unnerving for epidemiologists today is that with air travel, there’s just about no place on earth that isn’t fourteen hours from anyplace else. Add to this that an airliner, with its internal air re-circulation, is an almost ideal vector for airborne viruses. Aristotle stated that Men come together in cities for security; they stay together for the good life. But while Homeland Security is scanning our shoes and laptops for explosives for explosives they have no instrument capable of detection of the virus in our seatmate’s lungs.

Any city facing open seas will today only be hit by surprises, of both the natural and the gunship varieties. But the scenes in Manhattan a few days after Sandy – a third or more of the island in darkness, emergency crews digging and rebuilding, political leaders speaking from command bunkers, citizens adapting as best they can – should not be understood as a once- in-a-century or even once-in-a-decade exception. They are what we must come to expect regularly. The September 11 attacks, the 2003 blackout, Tropical Storm Irene, and Hurricane Sandy are events in a pattern. Technological, economic, political, and climate change all but guarantee that New York will be repeatedly disrupted during the twenty-first century in ways that it managed to avoid during the last one. [Steve Coll, www.newyorker.com, 2012]

And so also has emerged in the last three decades the prospect of a world of globally-interconnected hyper-urbanization, of exponentially expanding production and consumption of resources, that might be described as an open system disastrously re-ordering the components and relationships of the closed system in which it resides. What a better paradox it would be if what some have regarded as humankind’s greatest invention—the city—comes to play a major role in the terrors brought about by cultural conflict, mass migrations, famine, pandemic diseases, war, and catastrophic environmental events.

* * *

At such times and with such thoughts . . .

“Nothing exceeds the delight of one’s first immersion in Rome on a fine spring morning, even if it is not provoked by the sight of any particular work of art. The enveloping light can be of an incomparable clarity, throwing into gentle vividness every detail presented to the eye. First, the color which was not like the color of other cities I had been in. Not concrete color, not cold glass color, not the color of overburdened brick or harshly pigmented paint. Rather, the worn organic colors of the ancient earth and stone of which the city is composed the colors of limestone, the ruddy great of truth for, the warm discoloration of once – white marble and the speckled, rich surface of the marble known as pavonazzo, dappled with white spots and inclusions like the fat in a slice of mortadella. For an eye used to the more commonplace, uniform surfaces of the twentieth–century building, all this looks wonderfully, seductively rich without seeming overworked.”[Robert Hughes, Rome, Prologue, writing of his first visit to Rome in 1959]

I found myself rereading some of my favorite works from Robert Hughes on the occasion of his passing in 2012. The above passage selected for quotation is one that evoked a very similar memory of my own on a visit to Rome in the late 1970s. Like Hughes, I too have risen early from jet lag and found myself very much alone wandering on the Capitoline Hill at first light. I always answer “Rome” when I am asked what is my favorite city of the hundreds I have visited around the world. I answer unhesitatingly, not because of my Italian-American heritage, but because, as I wrote in a treatment for a (never produced) documentary titled “An American Priest in Rome” this city in particular elucidates for me the molar and the molecular of urbanism. I attempted to embrace its richness in its history in a panoramic sweep from the top of one of its most famous buildings. In the documentary treatment I wrote:

Following a Priest, our camera winds up a seemingly endlessly turning narrow stone staircase. As his breathing becomes more and more labored, we learn from our Narrator that we are following Father George Sullivan, an American priest writing a dissertation in theology. He has lived in Rome and worked in the Eternal City for several years. The priest and our camera finally emerge into the bright sunlight. We have ascended Michelangelo’s enormous dome of St. Peter’s Basilica and are on the roof of the world’s largest church. Beyond lies all of Rome.

When he has caught his breath, Fr. Sullivan gives us his summary perspective of the city he has grown to admire and love: “In the words of fellow Irishman James Joyce, ‘Rome reminds me of a man who lives by exhibiting to travelers his grandmother’s corpse.’”

From this high vantage, we zoom and then cut to various parts of Rome and some of its citizens in the streets as Fr. Sullivan relates that there are several corpses, several Romes; some parts exposed, some others more recondite. Interwoven in the fabric of the physical city, and often juxtaposed by historical events and everyday demands, are the Rome of the Republic (the Pantheon), the Rome of the Caesars (the Coliseum), the Rome of the Popes (the Vatican Palace), Renaissance Rome (the Palazzo Medici), Baroque Rome (the Piazza del Popolo), the Rome of Fascist Italy (the Foro Italico), and the Rome of today.

And we observe the people themselves, in whose blood courses, and in whose customs and features, are the traces of Sabine captives, orators and generals, Egyptian nobles, Greek physicians, Thracian gladiators, Gallic slaves, British conscripts, Gothic invaders, and the pilgrims who coursed to the city from along its imperial network of roads.

It is a city whose very name calls forth republicanism and tyranny, grandeur and disrepute, piety and worldliness, ingenuity and foolishness, and always the drama of a place formed by the sword and the spirit.

Rome, it now seems to me, has already given us an example of the perils of the urban imperium. It demonstrated that urbanism transcended political ideologies, race and ethnicity, even faith. Its driving spirit was not capitalism, nor democracy, but the very idea of itself—Rome—as the world, as the Pope still declaims: urbi et orbi. Its Pax Romana, over two hundred years of urban based conquest and enslavement might qualify Rome as the first “global” city.

Yet Hughes’s recollection of a Roman morning provides a more particularistic perspective on that city’s urbanism. This is the city we find when we turn urbanism inside out, or perhaps more accurately outside in. It is the city that we can discern the markings and evidence of individual lives, where the matrix of the city allows for expression in the form of communities, neighborhoods, individual dwellings, and where there is indication of the circadian, commonplace, comings and goings of urban life. It is that aspect of the city that expresses the fundamental distinction that took place in the first permanent settlements that broke with the long preceding period of hunting and gathering: the establishment of place.

However there are those who do not see even this fundamental existential dimension of urbanism as essential to the urban experience. For example, William Mitchell maintains that his concept of . . .

The City of Bits…[that] will be a city unrooted to any definite spot on the surface of the earth, shaped by connectivity and bandwidth constraints rather than by accessibility and land values, largely asynchronous in its operation, and inhabited by disembodied and fragmented subjects who exist as collections of aliases and agents. Its places will be constructed virtually by software instead of physically from stones and timbers, and they will be connected by logical linkages rather than by doors, passageways, and streets.

While I admit to doing much of my shopping on Amazon.com these days it does not delude me with the prospect, even the possibility, of a city “unrooted” to a space, to land, to a place. It is an incontestable fact of life that the two fundamental dimensions of existence are Time and Space. What exists is always somewhere, at some time. But for each of us these dimensions have particularity. Time and space become circumstance and place because it is experience that gives their intersection significance to us. It is another incontestable fact that every square foot of land on the face of the earth is geographically unique and territorially mutually exclusive. Check your GPS. A lot of the surface of the earth does not have much social significance other than its own unique coordinates. But there are places that do acquire social significance, which is what makes them places and not just spaces. A place is where something of significance and memorable happened. Ground Zero is a place. It has a placeness that radiates outward, where other land uses are in relation to their distance from or to Ground Zero. Jerusalem has placeness; Rome has placeness; Mecca had placeness; so does Omaha Beach in Normandy, Hollywood, and a lot more places we can think of. Some of them are quite personal, like happy places (where you met the love of your life), or sad places we prefer not to re-visit, and many share a collective memory. Place-making is a distinctly human activity, and we can become very attached and emotional about the places we make. Amazon may save a lot of time and trouble when shopping, but clicking on a cappuccino icon on your computer is not the same experience as being in a café, and “Face Time” lacks touch. Placeness is what gives a city its distinctive urbi et orbi.

But while the notion of a city that consists of bits of digital information is factually unsupportable, it is heuristically interesting for the reason that it returns urbanists to considering the fundamental questions about the city: why did we give up hunting and gathering for urbanism in the first place; how should we define its purposes; and do we have any idea or control over where it is going to take us.

It is those questions that no doubt led me to researching and compiling the first edition of The City. In many respects, I credit that experience with a shift in emphasis in my academic and personal life. Although my higher education, and especially my graduate work, had been focused on American urban policy, especially in those heady years of the new frontier, the early years of my teaching career overlapped with a great hiatus in advancement of urban policy begun in the Nixon years, further slowed by inflation and to oil recessions, leading to President Reagan’s “morning in America” in which we woke up to the prevailing notion that “government is not here to help you” and no attempt on its part to acquire revenue by means of taxation shall be looked upon with favor or legitimacy. It was therefore an apt opportunity for me to pursue long dormant desires to link my love of cities to my love of the arts and the humanities.

In some respects The City was my first step in that direction, a wide-ranging, willful romp through any literature, nonfiction and fiction, factual and fanciful, prosaic and poetic, that might have anything to say about cities and understanding them better than my erstwhile endeavors with statistics, legislation, and policy analysis. It inspired my extensive travel in foreign cities, abetted by my somewhat fraudulent posturing as an international tour guide for several years, and more legitimately by posts at the University of Paris in 1989 and 1999, Fulbright professorships at two universities in Hong Kong, and lecturing stints in China. In between, were broadening adventures in working with the late film director, Denis Sanders, and television producer/director, Jack Ofield, and three years writing, producing, and hosting the public radio program, Metropolitan Journal, at KPBS. But my enduring interest and affection for the city and urban life remain what is the common and continuous element. Even as I have turned to writing fiction in recent years I have found the “city” to be an irresistible “character.”

I am uncertain that I am any closer to fully grasping the protean and elusive entity we call the “city”; perhaps it is the pursuit that is the most interesting and enjoyable part of the process. But, in addition to the incontestable fact that we exist in Time and Space, and are always somewhere in a unique geographical “place,” I continue to hold that the city represents the opportunity for how we as individuals can express our abilities, our aspirations, ourselves. Needless to say, researching a book such as this deprives one of any sense of originality.

Not houses finely roofed or the stones of walls well-builded, nay nor canals and dockyards, make the city, but men able to use their opportunity. [Alcaeus, 5th C B.C.]

2012