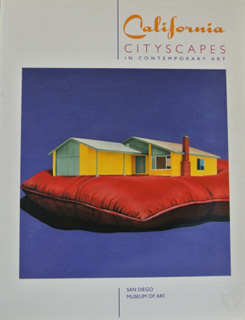

Mary Stofflet and James A. Clapp, California Cityscapes In Contemporary Art, New York: Universe Books, 1991.

A book about modern artists’ views of the contemporary city. The artwork presented is in a wide variety of media. It is 52 recent works by 27 authors. They are inspired by the visual richness of the constantly changing urban landscapes of California. Catalogue of the exhibition, artists’ biographies.

Overview Essay

PAINTING THE TOWN:

CITIES AND URBAN LIFE IN ART HISTORY

James A. Clapp, Ph.D.

The Long Prelude

From the cave paintings of pre-history to the present day, art has always been influenced by environment. For the past several millennia the urban environment has become increasingly influential in man’s experience and imagery. Regarded by some as a work of art in its own right, the City has become, at first gradually, and subsequently with spurts of dramatic suddenness, the experiential setting and frame of reference for many artists.

The City obviously generates great visual richness for artists. Its contrasts with the natural landscape, its varied morphology, its intensity and variety of texture, pattern, motion, and color, permute into an almost infinite number of visual and inspirational possibilities. These characteristics have been seized and interpreted in artistic modes ranging from the highly representational to the abstract, from the molar to the molecular, from the passive to the romantic, from the real to the imaginary.

There is another level at which the City has provided a rich array of thematic possibilities for artists. As the matrix and “container” for the most noble (and ignoble) manifestations of “civilization” the City challenges the artist to portray and interpret its mixed and complex symbols. The City simultaneously conveys man’s greatest achievements and failures, hope and despair, security and fear, community and loneliness, freedom and enslavement, harmony and discord, and power and impotence. In paraphrase of Dickens, the City often seems together the best and worst of places. Specific cities such as Babylon, Jerusalem, Rome, Athens, and New York, generate symbolic evocations that equal or exceed their historical and social significance—their very names calling forth vivid and powerful images and historical and literary associations. The inspirational potency of the City and the environment of urban life have been increasingly apprehended by artists, at first crudely and tentatively and, then, as the urbanization proceeded at an exponential pace with the industrial revolution, with greater frequency and range of interpretation.

The misty origins of the City still remain obscured in the rubble and ruins of very small settlements sealed in overgrown mounds in Mesopotamia and the Turkish Anatolian Plain. What for the present stands as perhaps the earliest example of townscape painting was discovered in the early 1960s on a wall shrine in an ancient Turkish city now called Catal Huyuk. The crude mural of pueblo-like, mud-hut structures was painted in cinnabar at a time that has been radiocarbon-dated at approximately 6,200 BC.

The Catal Huyuk fresco is noteworthy not only because it was an exceptional subject for its time, but also because its rarity probably owes to one of the major reasons townscape may have been avoided as a subject of painting—the difficulties of rendering the multiple planes of the city in accurate perspective. For centuries follow, with minor exceptions, the City was a rare theme for artists.

Cities on the Horizon

But the problem of perspective is only partial explanation. City life was itself exceptional, since the vast majority of people lived rural and pastoral lives. Indeed, for nearly a thousand years (from the 4th to 14th centuries), religion regarded the City as a place of poor repute. Scripture frequently portrayed the cities as a threat to man’s relationship with God: by association (Cain, the first city-builder, was also the first to commit homicide); by allegory (the Tower of Babel represented the folly of man’s attempt to reach heaven by technology rather than faith); and by the repetition of historical incidents in which the Hebrews fell from godly grace when they settled in cities (Sodom, Gomorrah, Jericho). Later, Augustine of Hippo posed the same dilemma for the Christian world. In The City of God the “heavenly city” was described as a transcendent entity, a spiritual city of different origin and meaning than the materialistic, self-interested “city of man.”

Not surprisingly, the bulk of painting up to the Renaissance dealt with religious and allegorical subject matter. But cities were growing in prominence, and while art patronage preferred religious subjects in the foreground, glimpses of cities began to appear in biblical scenes of landscapes and through windows and portals, especially in paintings in the Low Countries. In a Pieta by the School of Roger van der Weyden (ca. 1460) we spy an unidentified town on the horizon behind Christ’s cross. In other works by Van der Weyden, Campin, and van Eyck, the cities of Utrecht, Autun, Ghent, and other towns tantalizingly appear to decorate annunciations, nativities, and crucifixions, serving as “Flemished” Jerusalems, Nazareths and Bethlehems.

The City in Perspective

The Italian Renaissance, nurtured in the city-states of Tuscany, added a further dimension to artistic interest in cities. Related to the Renaissance interest in realistic painting, prospettiva (perspective) became a passion with artists such as Brunelleschi, Uccello and della Francesca, who used the streets and buildings of Florence to devise optical rules for accurate representation of objects in space, architecture, and idealized cities. Furthermore, the mercantile success of the city-states engendered a philosophical rapprochement with biblical anti-urbanism, which sometimes expressed itself in paintings of the Madonna holding models of her beloved Tuscan towns. But, more importantly, cityscapes were coming to be a fit subject for paintings in which the historical or religious event was more frequently moved to a secondary role.

Secularism played an even stronger role in the evolution of Dutch townscape in the 1700s. Having thrown off the yoke of Spain, Dutch towns flourished economically. If religious art patronage dropped off as a result, the proud burghers of Amsterdam, Delft, and Haarlem took up the slack by commissioning crisp, realistic views of their prosperous towns that needed no madonnas or saints for justification. The Berckhyde brothers turned them out by the dozen, and even painters of renown for portraiture and interiors, like Saenredem and Vermeer, produced views of streets and buildings.

Some of the lowlands painters migrated toward Italy where the light was better and the colors more vibrant, but also because the interest in the antique world and the growing popularity of the Grand Tour, on which the cities of Italy were an obligatory part of the itinerary, had created a new market for townscape. Artists like Gaspar Van Wittel (whose Italian works are signed “Vanvitelli”) produced views of the recently excavated Roman Forum, and piazzas and palaces, for the grand tourists, who, without benefit of cameras or postcards, needed visual proof for the folks back in London that they had indeed “been there.” By now, townscape was respectable enough to have acquired its own rubric. Briganti tells us:

. . . the term veduta itself, as it is most widely understood today—a topographical view depicting a site, a building, a picturesque corner a city, a panoramic townscape—is closely connected with the terminology of perspective. It derives from the same word meaning “the point to which the sight is directed” and thence “the appearance of a place,” the “prospect” of a place whether countryside, city or architectural subject, the picture or plane which is framed by the diverging lines of the visual pyramid.

It is appropriate therefore, if veduta was to have a master vedutisti, he should be Italian. Antonio Canale (1697-1768) fit the bill ideally, by both genealogy and location. A Venetian son of a theatrical scene painter, Canaletto, as he is better known, did more than any other artist to bring townscape vedute respectability and profitability. His Bacino di San Marco (1747-1750) illustrates his masterly technique and his inclination to the immediacy of the commonplace. Against the permanence of the piazzetta, campanile and Palazzo Ducale, which appear as they do to this day, he painted this view and others venues in his native city numerous times in different light to the delight of grand tourists (some of who might well have been captured in this scene gawking at the Bridge of Sighs).

The City of New Perspectives

By the turn into the 19th Century realistic townscape was established, but neither the City as subject, nor its representation in painting would remain stable. The new century, turbulent with social and political revolutions, the growth of industrialism, and rural to urban migration, ushered in what has been called “the age of great cities”. Pure townscape was founded on tranquil Dutch burgs, a greatly diminished Rome, and a Venice entering her dotage; the new century belonged to London, Paris and New York, burgeoning metropoles of energy, empire and futures of protean promise. The passive objectivity of vedute was not eclipsed, but given additional “perspectives” to address the manifold aspects of new urban realities. The new urban realities were to urge artists to be more that objective recorder of cities and urban life.

The momentous changes of the 1800s served to focus the attention of artists not so much on the urbanscape as a broad proscenium, but upon the drama of life in great cities in the vortex unprecedented social change. But the native-born artists of each city viewed their cities through the prisms of the salient social features of their city. “Urban” art in London remained largely representational, often narrative and tinged with social realism and moral message. A vedute scene might convey the Bank of England or other symbols of empire, but London painters also took thematic cues from the sooty engravings of Gustave Dore (or earlier still, Hogarth), and, of course, Dickens, for paintings about the homeless, street urchins, and the strains between the social classes, in sum, pigmenting Dickens’ “it was the best of times; it was the worst of times.”

No city underwent more startling growth during the 19th Century than New York. In addition to its population growth from waves of immigration (chronicled in several paintings of Castle Garden and Ellis Island), the rapid physical transformation of the city from one of low profile to a crosshatch of urban canyons often outdated street scenes before pigment was dry. Almost identical views of Broadway by two painters, separated by a decade, seem separated by a century of growth in density and architectural change. But, for the most part, New York’s native artists of the period contributed little in style and technique until the emergence of the “Ash Can School” in the 1910s.

As to 19th Century innovations in urban painting (and painting in general) that would lead to still bolder interpretations of the City the major credit must go to the painters in Paris in the latter years of the century. It was in Paris that painters began to look beyond the surface of urban subject matter to approach analytically the form, light, space, and substance of the city.

Of the three great cities Paris remained politically turbulent through much of the century, vacillating between empires, monarchy, republics, and, briefly, a socialist commune. Always a city upon which national leaders attempted to leave a personal imprint, the most significant such act was accomplished by Emperor Louis Napoleon between 1853 and 1870. The Paris we know today is for the most part the creation of Napoleon III and his chief prefect, Baron Eugene Haussmann, who were architects of the grand boulevards, the sewer system, almost all of the major parks, street tree planting, and massive residential building programs. New York’s Commissioners grid plan was designed for quick land sales, Paris’s plan was designed for grandeur (with some military objectives built in). Paris became The City of Lights.

Paris’ artistic movements, like its political movements, fluctuated during the 19th Century. Three major movements—romanticism, realism, and naturalism—rose to acceptance and subsequently fell out of favor. By the 1850s painters were uncomfortable with the precision and lifelike representation of the realist school, and were searching for novel means and techniques of visual expression to capture movement and gesture and a sense of the inner life of things. The Impressionists focused upon a range of subject matter, but they emphasized people and commonplace scenes. Monet in particular was much interested in the play of light on then architecture of cathedral and vaulted train stations. Pissarro’s urban scenes were more enlivened by human activity, as in his bustling views of boulevards. Degas and Renoir displayed a stronger tendency to get closer to human subject matter. Paris at this time was energized with the color and gaiety or cafe and street life. Color and light, all but synonymous in the optics of the impressionists, was given the most varied reflection, refraction and coalescence in the city. At the turn of the century Maximilien Luce’s view of Notre Dame, and Raoul Dufy’s La Seine a Paris evidenced that painting of the city could be seen in a new light.

Painting, of course, did not proceed independently of progressions in other fields. Science was delving beyond appearances in Nature, into its structure, into its processes. Pasteur uncovered the unseen processes of infection; Faraday the hidden bonds of electricity and magnetism; Roentgen discovered the x-rays which could penetrate and reveal the structure of matter; Freud and Jung brought forth the unconscious; and Darwin extended the arrow of time beyond the antique and classical ages. In a few years, Einstein would expose a new universe, not only beyond appearances, but also in seeming defiance of what experience and the senses had taught it to be. These advances were not without their influences upon music, dance, drama, literature, poetry, sculpture, and painting.

The City and the Machine

The 19th Century also forged a new relationship that influenced artistic interpretation of urbanism, between the City and the machine. Industrial technology, directly and indirectly, vastly altered the elements of urban iconography. Artificial illumination literally cast the city in a new light. With it, the City took on a new aspect and glow, multi-colored, glaring and blinking, though too often diminished and diffused by an atmosphere laden with the effluvia of factories and vehicles.

Perhaps even greater has been the impact of the machine upon motion. Mechanized vehicles brought noisy, blurred images, exaggerating and segregating the animation of the street. The quickened pace of the street is also reflected in the proliferation and gaudiness of signs, billboards, and traffic directions, all enlarged and visually intrusive to compete for attention in the accelerated movement through the city’s thoroughfares.

The machine also brought with it the mechanization of time. For millennia, human activity had been governed by circadian rhythms and the comings and goings of seasons; urban-industrial time regimented life to the clock and calendar, and substituted the factory whistle for the crowing of roosters and tolling church bells for the regulation of the workday. This regimentation of time into urban format altered the appearance of the City. The ebb and flow of activities in the industrial city’s streets takes on a synchronous tempo as the movements of workers, the openings and closings of shops, the swelling and thinning of traffic become regulated to the start of the work day, the rate of pay per hour, the arrival of the 5:05.

By the close of the century cities were the centers of economic and political power in industrial nations. In America, a country whose founding fathers thought would be an essentially rural nation, the transformation was dramatic. At the beginning of the century it was ten-percent urban, by 1920 half its population lived in urban places, in another sixty years less than ten-percent would be rural.

American Idioms

But if Americans increasingly moved their bodies to cities they left their hearts in the hinterlands. American political and intellectual sentiment was either ambivalent about cities or stridently negative. The works of Jefferson, Thoreau, Henry Adams, Henry James, Hawthorne, Dos Passos, and others, raised doubts about city life to outright romantic anti-urban sentiments. But at least they recognized its existence. Unlike their literary counterparts most American painters ignored cities and concentrated on “academic” tastes for landscape, portraiture, and allegorical subjects.

The first significant change in these attitudes emerged, somewhat appropriately, in the nation’s largest city. The painters of the Ash Can School in the early years of this century took as their subject matter the mundane, casual, everyday occurrences and scenes of the city. Though ash cans were indeed among some of the images that they selected of street and back-street life, the primary subjects of these realistic painters were people. The leader of this revolutionary group, originally formed in Philadelphia and variously referred to as the “Black Gang,” or less derisively, “The Eight,” was Robert Henri, whose personal philosophies celebrated the common man. Henri, who had studied with Thomas Anshutz, a disciple of the 19th Century realist Thomas Eakins, combined this background with a persuasive personality and an artistic manifesto which inspired artists such as George Luks, John Sloan, William Glackens, and Everett Shinn. As Henri put it: “The subject can be as it may, beautiful or ugly. The beauty of a work of art is in the work itself.” The City and its denizens, as they found it, suited this credo very well. They painted backyards, derelicts, bars, rooftops, and, as Sloan’s Italian Procession, New York, the occasional as well as the everyday life of the city, constituting what might loosely be called the first “school” of American urban painting.

The Ash Can School enjoyed modest critical success during the first decade, carving a niche for urban realism in American art; but their position as artistic revolutionaries was quickly eclipsed at the New York Armory Show of 1913 by the more stylistically diverse and bolder Europeans such as Picasso, Matisse, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Leger, Dufy, and its young star, Marcel Duchamp. Urban realism would have to take its place beside cubism, impressionism, futurism, and other avant garde styles that provided significantly different interpretations of urban life. Significant social events were also imminent.

Urban Realities and Rural Roots

World War I was, in effect, the death rattle of the old social order of the 19th Century. In Germany the “expressionists” took to depicting feelings of internal psychological turmoil with jumbled, apocalyptic urban views that reflected their misgivings about cities as well. Grosz, Dix, Meidner, and Max Beckmann, savagely satirized the moral breakdown in their country’s big cities, characterizing urbanites as greedy industrialists, corrupt politicians, and prostitutes. After the war Beckmann’s Mondaufgang uber dem Main (1925) is a scene of the cold and brooding city.

In America the crash of 1929 and the Depression shook the giddy optimism of urban ascendancy. The enormity of the event affected every dimension of society and its effect upon the painting of the American scene at large, and especially the imagery of the quality of life in its cities. American cities could no longer be viewed naively as faultless engines of a secure and splendid future and unabated material abundance. These social and economic circumstances figured in the two directions in American painting that dominated the 1930s, although it must be emphasized that the themes they dealt with transcend the consequences of a specific event like the Depression. “Regionalism,” which portrayed in easel and mural painting the social and geographic pluralism of the nation, produced paintings of people, environments, and life in small towns and rural areas as well as in large cities. “Social Realism,” the other major movement, frequently concentrated upon themes which dealt with social exploitation, class struggle, and alienation.

Social Realism received particular inspiration from the Depression. Philip Evergood’s American Tragedy recorded a blood encounter on Memorial Day 1937, which took place outside a steel mill in Chicago. Issac and Raphael Soyer portrayed despondent economic victims slumped in employment agencies and riding to nowhere in particular on subways. In W.P.A Sunday Ben Shahn evoked the disillusionment of idled, thick-handed workers lined up like the simple homes in their working-class neighborhood. The social realists put to pigment what Thomas Wolfe had put in words in his classic, You Can’t Go Home Again:

In other times, when painters tried to paint a scene of awful desolation, they chose the desert or heath of barren rocks, and there would try to picture man in his great loneliness—the prophet in the desert . . . But for a modern painter, the most desolate scene would be a street in almost any one of our great cities on a Sunday afternoon. Suppose a rather drab and shabby street in Brooklyn, not quite a tenement perhaps, and lacking therefore even the gaunt savagery of poverty, but a street of cheap brick buildings, warehouses and garages, with a cigar store or fruit stand or a barber shop on the corner. Suppose a Sunday afternoon in March—bleak, empty, slaty grey. And suppose a group of men, Americans of the working class, dressed in their “good” Sunday clothes—the cheap machine-made suits, the new cheap shoes, the cheap hats stamped out of universal grey. Just suppose this, and nothing more. The men hang around the corner before now and the, through the black and empty streets, a motor car goes flashing past, and in the distance they hear the cold mumble of the corner, waiting—waiting—waiting . . . for what? Nothing. Nothing at all. And this is what gives the scene its special quality of tragic loneliness, awful emptiness and utter desolation. Every modern city man is familiar with it.

If Wolfe was documenting the title of his book, the Regionalists were intent on making the point that, in the big American City at least, urban Americans were not home in the first place. Painters such as Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton claimed that the soul of America lay not in its metropoles, but in its small towns and rural hinterlands. Wood expressed this point of view not only in paintings which showed quaint small towns surrounded by curvaceous countryside that literalized the “mother earth” metaphor, and fields of topiary fruit trees, but also put the theme to words in his essay, “The Revolt Against the City.” Referring to his claim that America’s urban painters had been miming their European colleagues Wood argued that:

. . . urban growth, whose tremendous power was so effective upon the whole of American society, served, so far as art was concerned to tighten the grip of traditional imitativeness, for the cities were far less typically American than the frontier areas whose power they usurped. Not only were they the seats of the colonial spirit, but they were inimical to whatever was new, original and alive in the truly American spirit.

In fact, however, Wood often savagely satirized small town people in his more realistic portraits.

This ambivalence toward small towns may owe something to the adage that “familiarity breeds contempt” and that the small town could not live up to the rhapsodic ideals foisted upon it. For example, another Regionalist, Charles Burchfield often found small towns dreary, and frequently painted them in a gloomy weather at dusk. His Rainy Night (1930) compliments well his observation that “ . . .these buildings, with their staring, frightened eyes, have the look of going mad with loneliness.”

Loneliness was also increasingly recognized as a condition of big city life, but with a difference, as Donald Kuspit explains: “The way the city allows isolation, as a choice—as a village would not, with its demands of communal participation and conformity—is also a confirmation, however ironic, of its belief in individuality. The much lamented loneliness of the city is as much a symbol of its opportunity as of its oppression.”

The artist most deserving of singling out for his attention to urban isolation is Edward Hopper. In the famed Nighhawks and many other works Hopper posed solitary urbanites seated pensively at automats, peering silently from tenement windows, and silently side-by-side, separated by anonymity that urban life affords, and sometimes imposes. Hopper’s lonely, anonymous urbanites had their counterparts in novels and film noir. The big city, now an entity with a potentially sinister animus, could atomize its inhabitants, an exigent and unforgiving master that divided, conquered and enslaved those drawn to its wealth and promise.

Some saw the city this darkly, but by no means all. In popular culture Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelley danced and sang through and agreeable New York in film On The Town, fun city in the 1940s. If there was a contraposed perspective in painting it was that of Reginald Marsh, whose work, when contrasted with Hopper’s, is a testament to the notion that the City, rather than an objective construct, is, as many other things in life, in the eye of the beholder. Where Hopper saw city people as solitary beings, Marsh, painting in the same period and same city (New York), found crowds and conviviality. On the streets, on beaches, in subways, theatres, even under the grimy elevated railways, March portrayed urbanites in animated affirmation of the city’s manifold wonders.

Beyond Appearances

Since the close of WW II the reciprocal relationship between the art of urbanism and the American city has expanded and changed in every dimension. Indeed, it could be argued that the rich array of artistic styles in which the City and urban life have come to be interpreted has been both derivative of urban diversity and complexity. As noted at the outset of this essay, art is much influenced by environment. Today that environment is predominantly “urban”; and so the City is, demographically at least, the principal birthplace and environment of artists. In the period spanned by this broad overview the artistic theme of cities and urban life has evolved from one of rare exception to the commonplace. The City, is or has been, explored in every painting style or school, in such volume and variety, only the broadest of outlines can be suggested.

In the late 19th century artists began to explore urbanism beyond its surface characteristics. Impressionism revealed the city’s shifting and congealing hues, cubism its structural complexity, expressionism its psychological angst, surrealism its mystery. By the middle of this century painting styles began to reflect more directly the influence of urbanism. Technologies of communication spawned in the city, photography, television, and other media of mass communication, found expression in “pop art” and “abstract expressionism,” “super-realism” mimed the city’s technical virtuosity in its own detail and precision.

These various currents and eddies, sometimes contrasting, and often overlapping, opened a variety of new avenues of interpretation in the art of urbanism. From realism to abstraction, painters now expose the multiple dimensions of the City, as place, as idea, in particular, and in general. Each selects or abstracts from urban iconography images and forms that express alone, or in permutation, the city’s chimerical morphology, its social pluralism, its shifting economic structure, and its continually evolving culture. In so doing each re-creates the City in his or her own image.